Campbell Pryde, President and CEO, XBRL US

In December 2019, Congress passed the Grant Reporting Efficiency and Agreements Transparency (GREAT) Act (H.R. 150), which requires standardization of data reported by grants recipients. The GREAT Act aims to modernize reporting by grants recipients, reduce burden and compliance costs, and strengthen oversight and management of Federal grants. Standards must be established within two years of enactment (by December 2021). Standards for audit-related information reported as part of the Single Audit, within three years of enactment (December 2022).

The success of the GREAT Act depends on the data standards, and the implementation.

That's why it's important to have all the facts on how grantees report today, and on how the right standard can be applied to not only meet the "letter of the law", but more importantly, fulfill the promise of the GREAT Act.

What is the Single Audit process today?

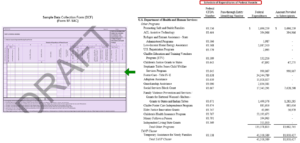

The Single Audit report, compiled in PDF format, is a large document containing financials, text, and schedules to report awarded amounts and audit findings, and may be prepared jointly by the grantee and their auditor. The PDF is submitted to the Federal Audit Clearinghouse (FAC), and then a subset of data that's already incorporated in the PDF (including the Schedule of Expenditures of Federal Awards and the Schedule of Findings and Questioned Costs) is separately keyed into an online form called the Data Collection Form (DCF) (shown below). Audit findings are generally reported as text but occasionally include tables.

Once the data is received at the FAC, data users obtain the grants data through the original PDF, along with the subset of data reported in the DCF, which is provided in text files. Data users must rely on a combination of parsing tools, along with manual rekeying and validation, to extract data from text files, or from the static PDF files.

The Data Model for this process, which defines what needs to be reported, is maintained in multiple places: 1) in the PDF file, 2) in the online DCF form, 3) in the data collection system, and 4) in the tools and processes used by data users to extract the data. That means that every time a change is made to reporting requirements, it has to be made in four separate places.

What does the GREAT Act aim to solve?

The difficulties with the current process that led to the GREAT Act affect everyone in the grants reporting supply chain.

Grantees and the auditors that support them: Data must be prepared twice. Duplicate data entry is burdensome and error-prone. The challenge of extracting clean data from PDF or text files means grantee data is often outdated, and decisions being made by agencies, investors, and researchers are based on old information.

Data users: Extracting data from electronic documents like PDFs or text files, is time-consuming, error-prone, and expensive. Data is old by the time it can be used, and there's a disincentive to perform robust (high volume) analysis, because it's too labor-intensive. Consequently, decisions about investments or policy-setting based on this data are less reliable, because they're less informed.

If there is a change to reporting requirements, data users have to revise their own data extraction process which makes analysis even more expensive.

Government agencies that collect and use the data: Agencies have the same timeliness and data extraction problems noted above. But in addition, the government is responsible for maintaining the online form and data collection system. If there are changes to reporting requirements, the agency must revise the online form (and make sure that everyone has the right version), plus upgrade the data collection system. This requires IT support and potentially outside vendor involvement. The expense often leads to deciding NOT to change reporting requirements, regardless of need.

The rigidity of the current system is a big deterrent to making rapid, knowledgeable decisions, and being able to change course when the situation demands it.

But do we really need data standards? Is there a cheaper short-cut that still meets the demands of the GREAT Act?

One proposed solution is for government agencies to build custom analytic tools so that data users can screen on and query the DCF-submitted data. After all, data keyed into the DCF form comes into the FAC in "machine-readable" form. In theory, those text files could be accessed through sophisticated querying, screening, and extraction tools to make it a lot easier for data users. While this would definitely be a step up from the current process, this is a short-term fix with many inherent problems, including:

It does not meet the requirements of the GREAT Act legislation. Section 6402 of the GREAT Act specifically names the requirements for data standards:

- Render information fully searchable and machine-readable

- Be non-proprietary

- Incorporate standards developed and maintained by voluntary consensus standards bodies

- Be consistent with and implement applicable accounting and reporting principles

These requirements will not be met by building custom analytics tools.

Custom tools are expensive to build and maintain. This approach will likely require outside vendor involvement. Changes in reporting requirements mean separate updates to the data collection system, the online form, the PDF requirements, and now, the custom analytics. That's because the Data Model is still maintained in four separate places, and will require IT, and very likely, ongoing vendor involvement.

Just as rigid a system as we have today. Lack of flexibility results in limits to change, inability to respond quickly, limited data, and often low-quality datasets.

What are data standards and how would they change the process?

A data standard, like eXtensible Business Reporting Language (XBRL), is not a product. It's not a technical format like XML, JSON, CSV, or HTML. It's a freely-available technical language with a consistent structure to unambiguously define the data reported.

The standard is based on a taxonomy - a digital dictionary of terms representing the data reported. A taxonomy for Single Audit data for example, contains terms like "Award Amount" and "Audit Findings". The taxonomy, which can be maintained by the government agency that collects the data, is the single source of the Data Model. The tools used to prepare, extract, and analyze data, and the data collection system itself, all reference the taxonomy to find out about reporting requirements. If a change is made in the taxonomy (which can be done by government data collectors without IT or vendor involvement), those changes can automatically be interpreted by preparation tools, the data collection system, and analytics tools, because grantees and data users rely on the online taxonomy as the only authoritative Data Model.

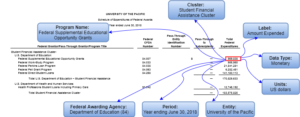

Data in a Single Audit report is complex. To understand the data requires knowing the parameters of each fact, such as label, definition, data type, time period, level of precision (thousands or actuals), and potentially other dimensional characteristics like name of the Federal Awarding Agency and name of the appropriate "cluster". Today, those characteristics are read by people extracting the data. The goal of the GREAT Act is for machines to be able to read the data without the need for manual (human) intervention.

XBRL is a freely-available, open, nonproprietary data standard, managed and maintained by a global, voluntary consensus standards body, and is structured to unambiguously convey the features of financial data, along with other data types. The diagram below shows metadata - data about the data - associated with a value like "569,838". XBRL captures and communicates that metadata along with the value to tell the whole story about the number. If that value was reported all by itself, no one would understand what it meant.

XBRL can also report other data types[1] needed for the Single Audit like text, integer, and even tables (and maintain the integrity of the table formatting).

The XBRL structure is combined with the means of "transporting" that content through a technical format, which could be CSV, JSON, XML or HTML. And because XBRL is used by millions of companies and governments worldwide, there are lots of tools already available to prepare, extract, store, and consume XBRL formatted data. More importantly, tools that are used today by grantees, auditors, governments, investors, researchers and other users, can be adapted to work with XBRL data - even tools like Excel spreadsheets.

Besides meeting the "letter of the law" when it comes to the GREAT Act, here's how a data standards program will build on, and improve the current process:

Ensures lowest possible costs for all stakeholders. Because XBRL can be used in lots of tools to prepare, store, extract, and analyze data; and the vendors of these tools compete in an open marketplace, supply chain participants have lots of low-cost, feature-rich applications from which to choose.

Government does not need to build or maintain custom analytics for users. Because the data is submitted by grantees in machine-readable format, data users and data providers can grab the files directly from the FAC, and extract the data in seconds. This is how the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) program works today.

Cheaper for government, much more flexible. Changes can be made easily without IT or outside vendor involvement. Plus, no need to build analytics for users.

View the infographic.

Watch the video.

[1] The XBRL standard can accommodate additional data types such as percent, per share, volume, and much more.