In 1974, the first Universal Product Code (UPC) was scanned in Troy, Ohio, automating what had been a manual process for recording sales. The first item scanned was a pack of Wrigley’s chewing gum. The UPC revolutionized the retail grocery business, using technology standards to wring costs out of a process that required the collection of massive amounts of data.

Just like a grocery store chain, a solar portfolio generates an enormous amount of data. Similarly, standards can be used to automate a manual process in the solar industry, eliminate huge volumes of paper, and reduce the cost of data collection.

Today, the solar industry is awash in data needed to evaluate potential investments in projects built around the world and to monitor their ongoing performance. And while the cost of installing solar has dropped by more than 60 percent over the past 10 years, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) has partnered with industry to squeeze more soft costs out of office work to bring solar energy in line with other electricity costs. The plan is to take a lesson from the grocery business and implement standards to automate what is today a paper-driven, manual process.

Why does the government care about solar?

Solar is no longer solely the interest of the environmentally conscious. The U.S. solar industry represents $15-20 billion of annual investment. The U.S. installed 4,143 megawatts (MW) of solar photovoltaic in the third quarter of 2016, reaching 35.8 gigawatts total, installed capacity, enough to power 6.5 million American homes. More importantly, nearly 209,000 Americans work in solar — more than double the number in 2010 with over 9,000 companies spread across every state. By 2020, the number of workers is projected to double to more than 420,000. Solar jobs have surpassed the number of jobs in coal mining and even in oil and gas extraction as you can see in the chart below from SEIA, the Solar Energy Industry Association.

Why so much data in solar projects?

Project finance is a common method to fund large solar power projects and portfolios of smaller, distributed generation solar projects. Investors can easily use the tax incentives to reduce their tax bills. Project finance involves creating a project company that is a separate business entity from the project developer or the investor. As a separate entity, the project company takes on the project’s liabilities and enters into the contractual arrangements with the project’s various parties, including construction companies, banks, asset managers, equipment suppliers, and operators.

Project finance arrangements come in various flavors, from sales leaseback to inverted lease to partnership flip. But regardless of the name, they all involve multiple players and, of course, substantial amounts of data communicated back and forth over what is usually a multi- (20-25) year timeline.

Wells Fargo has invested more than $4 billion in the solar and wind markets. The data flow for a typical tax-equity investor’s solar project origination and financing process requires approximately 100 separate files passed among numerous players. Each project requires dozens of agreements, such as an Engineering Procurement Construction Agreement, Master Services Agreement, and Limited Liability Company Agreement.

Each contract contains data that must be collected and reviewed. A best practice is to use “like” documents, contracts that are the same for each project in a fund or portfolio, and have those point to “reference” documents that contain unique reference values for each project. Yet the strain of handling the massive volume of documents and data is so great that it could be considered investors’ greatest obstacle to scaling solar project finance, particularly for portfolios of distributed generation projects such as commercial buildings and homes.

The project developer collects data from multiple parties into a data room. These files are accessed by another set of individuals who may use different pieces of information for their own due diligence review. This compiled data and analysis flows through to create an initial origination request.

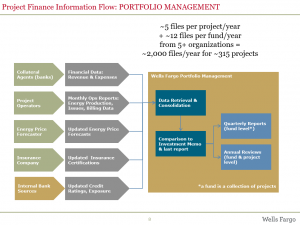

Once a project or portfolio of projects is funded, the reporting is typically handed off to the portfolio management team that provides ongoing monitoring. The data from multiple projects must be continually collected and monitored over the project’s investment term, which can be as short as seven years or as long as 25 years, depending on the finance structure.

Portfolio managers spend a lot of time reviewing documents, accessing online portals, and manually extracting individual data points to be used in analysis, and in quarterly or annual reviews. Many different aspects of the project must be monitored including the amount of energy produced, payments to operators and contractors, revenue generated, and performance metrics on the numerous pieces of equipment in the installation, such as PV modules, trackers and inverters. Today, this process is manual and time–intensive. It threatens investors’ ability to scale to keep pace with the demand for solar project finance, particularly for portfolios of small, distribution generation solar projects.

What can data standards do?

One of the most valuable lessons the solar industry can adopt from the grocery business is using robust standards to handle substantial amounts of data. The Department of Energy, through its Orange Button program, is partnering with industry players from solar, finance, accounting, and software to develop data standards for the massive amount of reporting needed for solar financing. The project, slated to run through 2018, brings together industry stakeholders to build a data taxonomy, covering finance, design, operations, construction, and deployment. The goal of the program is to reach 60 percent industry-wide adoption.

The XBRL (eXtensible Business Reporting Language) standard was chosen as the underlying technology standard, because it is an open, freely available, global standard. Although XBRL was designed specifically for financial data, it is also able to accommodate other numeric and non-numeric data. XBRL is widely used around the world, most notably in the U.S. for public company financial reporting to the Securities and Exchange Commission. Because of this requirement, a comprehensive set of data fields for financial reporting is already available (and maintained by the FASB, the U.S. accounting standard setter) and is being leveraged in the Orange Button project. The taxonomy will also incorporate existing energy-specific standards, such as IECRE for Renewable Energy and other kinds of solar data standards used by credit rating agencies, accounting firms, and others.

The Bottom Line

Use of the XBRL standard will make data computer-readable and enable automation. Data buried in performance tracking reports and contracts will be easy for users to extract and consume. Automation reduces labor costs and allows portfolio managers and investment analysts to do the work for which they were hired – monitoring, forecasting, and safeguarding the performance of solar investments. Standards also can increase the accuracy of reported information because validation checks can be created to evaluate data against a set of metrics as it’s reported and again as it’s consumed.

Standards as simple as the UPC code have been proven time and again to reduce costs. The solar industry, in alignment with the DOE, is on its way to making solar energy even more affordable for business, for government, and for American households.

Want to learn more and get involved? Visit our solar page.

Michelle Savage is vice president of Communications for XBRL US, the national consortium for XBRL business reporting standards. She can be reached at michelle.savage@xrbl.us. Jonathan Previtali is a vice president with the Environmental Finance Group at Wells Fargo, with expertise in utility scale solar power, distributed generation solar, and wind power projects. He can be reached at jonathan.m.previtali@wellsfargo.com.

In 1974, the first Universal Product Code (UPC) was scanned in Troy, Ohio, automating what had been a manual process for recording sales. The first item scanned was a pack of Wrigley’s chewing gum. The UPC revolutionized the retail grocery business, using technology standards to wring costs out of a process that required the collection of massive amounts of data.

Just like a grocery store chain, a solar portfolio generates an enormous amount of data. Similarly, standards can be used to automate a manual process in the solar industry, eliminate huge volumes of paper, and reduce the cost of data collection.

Today, the solar industry is awash in data needed to evaluate potential investments in projects built around the world and to monitor their ongoing performance. And while the cost of installing solar has dropped by more than 60 percent over the past 10 years, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) has partnered with industry to squeeze more soft costs out of office work to bring solar energy in line with other electricity costs. The plan is to take a lesson from the grocery business and implement standards to automate what is today a paper-driven, manual process.

Why does the government care about solar?

Solar is no longer solely the interest of the environmentally conscious. The U.S. solar industry represents $15-20 billion of annual investment. The U.S. installed 4,143 megawatts (MW) of solar photovoltaic in the third quarter of 2016, reaching 35.8 gigawatts total, installed capacity, enough to power 6.5 million American homes. More importantly, nearly 209,000 Americans work in solar — more than double the number in 2010 with over 9,000 companies spread across every state. By 2020, the number of workers is projected to double to more than 420,000. Solar jobs have surpassed the number of jobs in coal mining and even in oil and gas extraction as you can see in the chart below from SEIA, the Solar Energy Industry Association.

Why so much data in solar projects?

Project finance is a common method to fund large solar power projects and portfolios of smaller, distributed generation solar projects. Investors can easily use the tax incentives to reduce their tax bills. Project finance involves creating a project company that is a separate business entity from the project developer or the investor. As a separate entity, the project company takes on the project’s liabilities and enters into the contractual arrangements with the project’s various parties, including construction companies, banks, asset managers, equipment suppliers, and operators.

Project finance arrangements come in various flavors, from sales leaseback to inverted lease to partnership flip. But regardless of the name, they all involve multiple players and, of course, substantial amounts of data communicated back and forth over what is usually a multi- (20-25) year timeline.

Wells Fargo has invested more than $4 billion in the solar and wind markets. The data flow for a typical tax-equity investor’s solar project origination and financing process requires approximately 100 separate files passed among numerous players. Each project requires dozens of agreements, such as an Engineering Procurement Construction Agreement, Master Services Agreement, and Limited Liability Company Agreement.

Each contract contains data that must be collected and reviewed. A best practice is to use “like” documents, contracts that are the same for each project in a fund or portfolio, and have those point to “reference” documents that contain unique reference values for each project. Yet the strain of handling the massive volume of documents and data is so great that it could be considered investors’ greatest obstacle to scaling solar project finance, particularly for portfolios of distributed generation projects such as commercial buildings and homes.

The project developer collects data from multiple parties into a data room. These files are accessed by another set of individuals who may use different pieces of information for their own due diligence review. This compiled data and analysis flows through to create an initial origination request.

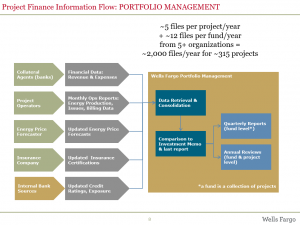

Once a project or portfolio of projects is funded, the reporting is typically handed off to the portfolio management team that provides ongoing monitoring. The data from multiple projects must be continually collected and monitored over the project’s investment term, which can be as short as seven years or as long as 25 years, depending on the finance structure.

Portfolio managers spend a lot of time reviewing documents, accessing online portals, and manually extracting individual data points to be used in analysis, and in quarterly or annual reviews. Many different aspects of the project must be monitored including the amount of energy produced, payments to operators and contractors, revenue generated, and performance metrics on the numerous pieces of equipment in the installation, such as PV modules, trackers and inverters. Today, this process is manual and time–intensive. It threatens investors’ ability to scale to keep pace with the demand for solar project finance, particularly for portfolios of small, distribution generation solar projects.

What can data standards do?

One of the most valuable lessons the solar industry can adopt from the grocery business is using robust standards to handle substantial amounts of data. The Department of Energy, through its Orange Button program, is partnering with industry players from solar, finance, accounting, and software to develop data standards for the massive amount of reporting needed for solar financing. The project, slated to run through 2018, brings together industry stakeholders to build a data taxonomy, covering finance, design, operations, construction, and deployment. The goal of the program is to reach 60 percent industry-wide adoption.

The XBRL (eXtensible Business Reporting Language) standard was chosen as the underlying technology standard, because it is an open, freely available, global standard. Although XBRL was designed specifically for financial data, it is also able to accommodate other numeric and non-numeric data. XBRL is widely used around the world, most notably in the U.S. for public company financial reporting to the Securities and Exchange Commission. Because of this requirement, a comprehensive set of data fields for financial reporting is already available (and maintained by the FASB, the U.S. accounting standard setter) and is being leveraged in the Orange Button project. The taxonomy will also incorporate existing energy-specific standards, such as IECRE for Renewable Energy and other kinds of solar data standards used by credit rating agencies, accounting firms, and others.

The Bottom Line

Use of the XBRL standard will make data computer-readable and enable automation. Data buried in performance tracking reports and contracts will be easy for users to extract and consume. Automation reduces labor costs and allows portfolio managers and investment analysts to do the work for which they were hired – monitoring, forecasting, and safeguarding the performance of solar investments. Standards also can increase the accuracy of reported information because validation checks can be created to evaluate data against a set of metrics as it’s reported and again as it’s consumed.

Standards as simple as the UPC code have been proven time and again to reduce costs. The solar industry, in alignment with the DOE, is on its way to making solar energy even more affordable for business, for government, and for American households.

Want to learn more and get involved? Visit our solar page.

Michelle Savage is vice president of Communications for XBRL US, the national consortium for XBRL business reporting standards. She can be reached at michelle.savage@xrbl.us. Jonathan Previtali is a vice president with the Environmental Finance Group at Wells Fargo, with expertise in utility scale solar power, distributed generation solar, and wind power projects. He can be reached at jonathan.m.previtali@wellsfargo.com.